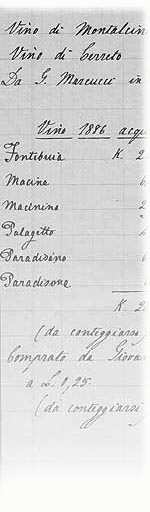

|

The Padelletti family is one of the oldest of the old town of Montalcino.

Down the generations they were physicians, lawyers, judges and University

professors and often because of their work or because of political

defeats, they had to live in other towns, but a member of the family

always remained in Montalcino to take care of the land the family

owned. The bond with their land is strong and has remained unbroken.

They always took an active part in the political life of the town.

For many centuries there was a feud between the Papacy and the German

Holy Roman Emperors about the ownership of Tuscany. As the Padelletti

family sided with the Emperors, in the 13th century the head of

the family had to take refuge in Germany at the court of the Staufers

and those who remained had, for a long time, to keep very quiet.

But, in the year 1529, when Montalcino fought the Spaniards for

independence, a certain Giovanni Padelletti came back to take part

in the defense. As he was an architect, he was given responsibility

for the defense of a part of the town walls and two gates (which

still belong to the descendands of the family). However in the year

1559, the Spaniards defeated the King of France and, by the treaty

of Chateau Cambresis, Montalcino was given to the Spaniards, who

ceded it to the Medici. Again the Padelletti family had to lie low

and much of their property was confiscated. Nevertheless, by the

year 1572 the Padelletti family was again listed among the owners

of vineyards, olive groves and

tillable land who were paying a tithe to the Hospital of Montalcino.

Since then, the name Padelletti vineyards and wine have gone together.

Already by the 16th century, Montalcino was famed for the specialties

"Moscadelletto di Montalcino" and "Vinsanto".

The bulk of the red wine production was made following the same

systems as Chianti: that is using several types of red and white

grapes together. The primary reason for this was that having vineyards

with grapes maturing in different periods, the dangers from late

frosts and hail were reduced. Another reason was that the "Sangiovese"

grape did yield a very good wine but only after some years of ageing.

The addition of white grapes enabled the

production of a drinkable wine after only a few months. The landowners

were forced by the prevailing poverty to turn their crops into money

as soon as possible. The markets were also limited by the lack of

roads suitable for horse-and ox-drawn carts. Over the centuries,

however, because of the climate and soil, it was noticed that the

Sangiovese grape had changed and could produce a wine that differed

from that obtained from the same type of grape in other parts of

the country. However, it still remained imperative to age the wine

for several years to achieve the best flavour and taste, and, yet

this ageing process itself poses another problem. Normally the wine

casks were made of chestnut wood, abundant in the region, but this

wood contains a lot of tannin which, in the long run, gave the wine

a disagreeable taste. To avoid this drawback, the wood from a special

oak, that did not grow in the region, had to be used. And it was

costly. And the resulting expense limited the possible sales. So,

this wine,

special wine, was made only for the landowners themselves and some

of their friends. It was noted that, when correctly aged, one of

the characters of this special wine was that it took on a reddish-brown

colour instead of the ruby red of Chianti - hence the name "Brunello"

(Browny). This wine was of no

commercial interest. So, it did exist, but in very limited quantities,

and was never sold (marketed). For a couple of centuries the Padelletti

family

prospered producing magistrates, bishops, many notaries and doctors.

The 19th century was not kind to the main branch of the family.

Antonio was

The Padelletti family is one of the oldest of the old town of Montalcino.

Down the generations they were physicians, lawyers, judges and University

professors and often because of their work or because of political

defeats, they had to live in other towns, but a member of the family

always remained in Montalcino to take care of the land the family

owned. The bond with their land is strong and has remained unbroken.

They always took an active part in the political life of the town.

For many centuries there was a feud between the Papacy and the German

Holy Roman Emperors about the ownership of Tuscany. As the Padelletti

family sided with the Emperors, in the 13th century the head of

the family had to take refuge in Germany at the court of the Staufers

and those who remained had, for a long time, to keep very quiet.

But, in the year 1529, when Montalcino fought the Spaniards for

independence, a certain Giovanni Padelletti came back to take part

in the defense. As he was an architect, he was given responsibility

for the defense of a part of the town walls and two gates (which

still belong to the descendands of the family). However in the year

1559, the Spaniards defeated the King of France and, by the treaty

of Chateau Cambresis, Montalcino was given to the Spaniards, who

ceded it to the Medici. Again the Padelletti family had to lie low

and much of their property was confiscated. Nevertheless, by the

year 1572 the Padelletti family was again listed among the owners

of vineyards, olive groves and

tillable land who were paying a tithe to the Hospital of Montalcino.

Since then, the name Padelletti vineyards and wine have gone together.

Already by the 16th century, Montalcino was famed for the specialties

"Moscadelletto di Montalcino" and "Vinsanto".

The bulk of the red wine production was made following the same

systems as Chianti: that is using several types of red and white

grapes together. The primary reason for this was that having vineyards

with grapes maturing in different periods, the dangers from late

frosts and hail were reduced. Another reason was that the "Sangiovese"

grape did yield a very good wine but only after some years of ageing.

The addition of white grapes enabled the

production of a drinkable wine after only a few months. The landowners

were forced by the prevailing poverty to turn their crops into money

as soon as possible. The markets were also limited by the lack of

roads suitable for horse-and ox-drawn carts. Over the centuries,

however, because of the climate and soil, it was noticed that the

Sangiovese grape had changed and could produce a wine that differed

from that obtained from the same type of grape in other parts of

the country. However, it still remained imperative to age the wine

for several years to achieve the best flavour and taste, and, yet

this ageing process itself poses another problem. Normally the wine

casks were made of chestnut wood, abundant in the region, but this

wood contains a lot of tannin which, in the long run, gave the wine

a disagreeable taste. To avoid this drawback, the wood from a special

oak, that did not grow in the region, had to be used. And it was

costly. And the resulting expense limited the possible sales. So,

this wine,

special wine, was made only for the landowners themselves and some

of their friends. It was noted that, when correctly aged, one of

the characters of this special wine was that it took on a reddish-brown

colour instead of the ruby red of Chianti - hence the name "Brunello"

(Browny). This wine was of no

commercial interest. So, it did exist, but in very limited quantities,

and was never sold (marketed). For a couple of centuries the Padelletti

family

prospered producing magistrates, bishops, many notaries and doctors.

The 19th century was not kind to the main branch of the family.

Antonio was  killed in a riding accident; his son, Pierfrancesco,

after having held one of the highest positions in the Grand Duchy

of Tuscany, died suddenly while still young. Of Pierfrancesco’s

sons; Guido, who was a professor at the universities of Pavia, Bologna

and Rome, died before he was 35 of wounds he suffered when fighting

with Garibaldi for the independence of Italy; Dino, who was a professor

at Naples university, died equally young, of the plague. There remained

Professor Domenico, Pierfrancesco’s brother, who was Rector

of Pisa University and Carlo Augusto, Guido’s son, who was

still an infant. Professor Domenico Padelletti retired to Montalcino

to take care of the family patrimony and assist his young great-nephew.

Professor Domenico made many improvements. He planted new vineyards

and olive groves and bought more land. So, by the time Carlo Augusto

reached 21, he inherited a large estate of well-kept land from his

great-uncle. Carlo Augusto intensely pursued a wide variety of activities.

Besides obtaining no less than four doctorates from various universities,

he was a diplomat, a judge, a lawyer and a physician. He was also

an industrialist creating many new industries in a region that had

none and which seemed to aspire to nothing beyond agriculture. The

population

of Montalcino was poor with high unemployment, and whose only source

of power was human or animal. By-passing steam power completely,

Carlo Padelletti chose, instead, to back the newly discovered electrical

power

generated by that new source of energy, the internal combustion

engine. As fuel, he used the gases generated by the burning of waste

from the timber industry. All this was before the end of the 19th

century. In fact, by 1899 Carlo Augusto Padelletti had created a

good electricity supply. As a first step, he

lit the town of Montalcino with electricity when Rome and Florence

were still illuminated by gas. Then, using his abundant financial

resources, he started setting up industries that would increase

the profitability of Montalcino’s

agricultural production. A lot of wheat and cereals were produced,

but it was only in winter, when the streams were full enough to

drive the water-wheels, that wheat flour could be ground in the

mills. So, he built an electrically-powered flour mill in Montalcino,

and an olive press and a saw mill. When he needed more bricks, he

built a brick furnace. He developed an industry to utilize forestry

by-products. Then he started a large printing and book-binding industry

and, finally, a movie theatre! During this time, Carlo Augusto Padelletti

had also modernized agriculture. He introduced iron ploughs,

internal combustion tractors and harvesting machines. In the meantime,

the creation of the railway network somewhat improved the opportunities

for the export of Montalcino’s agricultural produce even though

Montalcino’s hill-top position did reduce this benefit to some

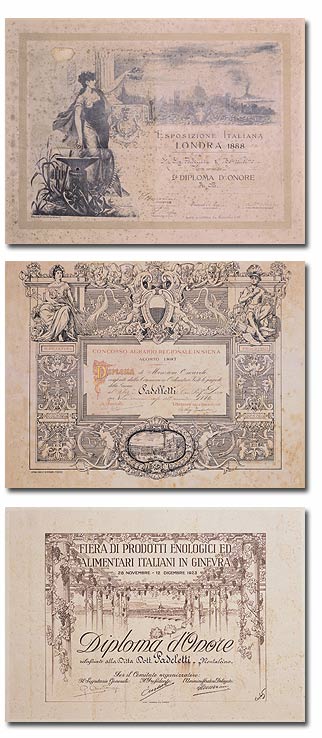

extent. Carlo Augusto Padelletti also did much to improve the wines

of Montalcino, presenting wine and olive oil at many Italian exhibitions

and also winning prizes abroad from London to Geneva. He opened

a sales office in Geneva to optimize the distribution of Montalcino

wines. Like other far-sighted landowners, he continued to produce

Brunello but always in small quantities. The vineyards were still

a mixture of grape varieties and the Brunello grapes were gathered

before the main harvest. It had been noted that the alluvial soils

at the foot of the Montalcino hill

produced the best Brunello, strong but agreeable. The wine from

the south slopes was too strong and from the higher slopes, too

light. Therefore,

the

landowners on these particularly favoured locations (the Biondi

at "La Chiusa" estate; the Padelletti at "Paradisi"

and "Rigaccini"; the Anghirelli at "Il Cigaleto")

produced the best Brunellos but never viewed it as a commercially

viable enterprise. It was true that Brunello could be aged for longer

than most other wines but, because of its high price in comparison

with better known wines and because of the general level of poverty,

making Brunello on a large scale was not a winning proposition.

Another factor was the dwindling production of grapes following

the destruction of the vineyards by phylloxera together with the

rumors of war and later, the war itself which discouraged the owners

from planting new vineyards, In 1925, Carlo Augusto Padelletti,

unable to cope with all his initiatives because of his age, had,

with some other

landowners, founded a "Cantina Sociale" and its management

was entrusted to Dr. Tancredi Biondi. Just before the Second World

War this winery had to be

dissolved because of the lack of grapes. After the war there were

almost no vineyards left in Montalcino. Some courageous landowners

then started replanting, but only Brunello grapes. The economic

situation improved rapidly and the "Italian Miracle" took

place. There was money for both investment and consumption. New

and improved vineyards were planted and new cellars with new oak

casks were made. Demand was met by increased production, but far

beyond the boundaries always considered most suitable for Brunello.

Dr. Avv. Carlo Augusto Padelletti, by now over 80, entrusted the

management of his land to his son, Guido, who continue d with the

planting of a vineyard in the original location where the best Brunello

had been produced, years before. After the division of the paternal

estate with his brothers, he was left with the "Rigaccini"

estate. He has 6 hectares of beautiful vineyards but, because of

his professional commitments abroad, he limits himself to the production

of

splendid Brunello grapes, using only one fifth of the best of these

to make an average of 8.000 bottles a year and selling the remainder

to other Brunello

producers. His cellar is under the family house in Via Padelletti,

on the city walls where so many generations of his family have lived.

Guido Padelletti still thinks that quantity is the enemy of quality

and tries to maintain the high

standards set by his own ancestors. killed in a riding accident; his son, Pierfrancesco,

after having held one of the highest positions in the Grand Duchy

of Tuscany, died suddenly while still young. Of Pierfrancesco’s

sons; Guido, who was a professor at the universities of Pavia, Bologna

and Rome, died before he was 35 of wounds he suffered when fighting

with Garibaldi for the independence of Italy; Dino, who was a professor

at Naples university, died equally young, of the plague. There remained

Professor Domenico, Pierfrancesco’s brother, who was Rector

of Pisa University and Carlo Augusto, Guido’s son, who was

still an infant. Professor Domenico Padelletti retired to Montalcino

to take care of the family patrimony and assist his young great-nephew.

Professor Domenico made many improvements. He planted new vineyards

and olive groves and bought more land. So, by the time Carlo Augusto

reached 21, he inherited a large estate of well-kept land from his

great-uncle. Carlo Augusto intensely pursued a wide variety of activities.

Besides obtaining no less than four doctorates from various universities,

he was a diplomat, a judge, a lawyer and a physician. He was also

an industrialist creating many new industries in a region that had

none and which seemed to aspire to nothing beyond agriculture. The

population

of Montalcino was poor with high unemployment, and whose only source

of power was human or animal. By-passing steam power completely,

Carlo Padelletti chose, instead, to back the newly discovered electrical

power

generated by that new source of energy, the internal combustion

engine. As fuel, he used the gases generated by the burning of waste

from the timber industry. All this was before the end of the 19th

century. In fact, by 1899 Carlo Augusto Padelletti had created a

good electricity supply. As a first step, he

lit the town of Montalcino with electricity when Rome and Florence

were still illuminated by gas. Then, using his abundant financial

resources, he started setting up industries that would increase

the profitability of Montalcino’s

agricultural production. A lot of wheat and cereals were produced,

but it was only in winter, when the streams were full enough to

drive the water-wheels, that wheat flour could be ground in the

mills. So, he built an electrically-powered flour mill in Montalcino,

and an olive press and a saw mill. When he needed more bricks, he

built a brick furnace. He developed an industry to utilize forestry

by-products. Then he started a large printing and book-binding industry

and, finally, a movie theatre! During this time, Carlo Augusto Padelletti

had also modernized agriculture. He introduced iron ploughs,

internal combustion tractors and harvesting machines. In the meantime,

the creation of the railway network somewhat improved the opportunities

for the export of Montalcino’s agricultural produce even though

Montalcino’s hill-top position did reduce this benefit to some

extent. Carlo Augusto Padelletti also did much to improve the wines

of Montalcino, presenting wine and olive oil at many Italian exhibitions

and also winning prizes abroad from London to Geneva. He opened

a sales office in Geneva to optimize the distribution of Montalcino

wines. Like other far-sighted landowners, he continued to produce

Brunello but always in small quantities. The vineyards were still

a mixture of grape varieties and the Brunello grapes were gathered

before the main harvest. It had been noted that the alluvial soils

at the foot of the Montalcino hill

produced the best Brunello, strong but agreeable. The wine from

the south slopes was too strong and from the higher slopes, too

light. Therefore,

the

landowners on these particularly favoured locations (the Biondi

at "La Chiusa" estate; the Padelletti at "Paradisi"

and "Rigaccini"; the Anghirelli at "Il Cigaleto")

produced the best Brunellos but never viewed it as a commercially

viable enterprise. It was true that Brunello could be aged for longer

than most other wines but, because of its high price in comparison

with better known wines and because of the general level of poverty,

making Brunello on a large scale was not a winning proposition.

Another factor was the dwindling production of grapes following

the destruction of the vineyards by phylloxera together with the

rumors of war and later, the war itself which discouraged the owners

from planting new vineyards, In 1925, Carlo Augusto Padelletti,

unable to cope with all his initiatives because of his age, had,

with some other

landowners, founded a "Cantina Sociale" and its management

was entrusted to Dr. Tancredi Biondi. Just before the Second World

War this winery had to be

dissolved because of the lack of grapes. After the war there were

almost no vineyards left in Montalcino. Some courageous landowners

then started replanting, but only Brunello grapes. The economic

situation improved rapidly and the "Italian Miracle" took

place. There was money for both investment and consumption. New

and improved vineyards were planted and new cellars with new oak

casks were made. Demand was met by increased production, but far

beyond the boundaries always considered most suitable for Brunello.

Dr. Avv. Carlo Augusto Padelletti, by now over 80, entrusted the

management of his land to his son, Guido, who continue d with the

planting of a vineyard in the original location where the best Brunello

had been produced, years before. After the division of the paternal

estate with his brothers, he was left with the "Rigaccini"

estate. He has 6 hectares of beautiful vineyards but, because of

his professional commitments abroad, he limits himself to the production

of

splendid Brunello grapes, using only one fifth of the best of these

to make an average of 8.000 bottles a year and selling the remainder

to other Brunello

producers. His cellar is under the family house in Via Padelletti,

on the city walls where so many generations of his family have lived.

Guido Padelletti still thinks that quantity is the enemy of quality

and tries to maintain the high

standards set by his own ancestors.

|